MÚSICA PROJETADA PROJECTED MUSIC

Na Matéria do Diálogo

On the Subject of Dialogue

Estreia Premiere

28.11.2025 20:00

Sexta-feira Friday

Idanha-a-Nova

Centro Cultural Raiano

Música: Aquilo que nos faz parar (ou mover), que nos obriga a sentir (ou dormir), que nos percorre.

Projectada: Que se projecta, que invade e expande e que cruza imagem, luz e tempo.

Music: That which makes us pause (or move), that compels us to feel (or sleep), that flows through us.

Projected: That which projects, invades, expands, and intersects with image, light, and time.

Projecto BANDURRA 43

Reinterpretação da Viola Beiroa de Manuel Moreira (Salvador, 1891-1970), Penha Garcia. Um diálogo com a viola de mão de Belchior Dias (Lisboa, 1581).

Project BANDURRA 43

Reinterpretation of Manuel Moreira's Viola Beiroa (Salvador, 1891-1970), Penha Garcia. A dialogue with Belchior Dias' renaissance guitar (Lisbon, 1581).

Um projecto original

An original project by

Filipe Faria

\Arte das Musas

Em parceria com

In partnership with

Município de Idanha-a-Nova

\UNESCO Creative City of Music

Apoio

Support

República Portuguesa - Cultura

\Direção-Geral das Artes

+ Apoios

Supports

Museu Nacional de Etnologia, Direção-Geral do Património Cultural, INET-md Centro de Estudos em Música e Dança (FCSH/UNL), Núcleo Etnográfico da Lousa, Lousarte - Associação Cultural e Etnográfica da Lousa

Edição

Edition

Arte das Musas

Colecção

Collection

Etno Series Parceria

Partnership

O Homem – Colectivo

Filme

Film

Na matéria do diálogo

On the subject of dialogue

Realização, câmara e som Direction, camera and sound Filipe Faria

Ao mesmo tempo, ferramenta e obra de arte EXCERTO

Filipe Faria

A tapeçaria bordada pelos elementos do património musical português é um reflexo do cruzamento de fios culturais e históricos que moldaram a identidade musical do país ao longo dos séculos. O nosso instrumentário musical popular, tal como o conhecemos hoje, é o resultado da contaminação inevitável de viagens, gostos pessoais, experiências individuais ou necessidades colectivas. A evolução é inevitável — hoje não tenho aquela madeira, amanhã consigo outra, hoje pedem-me que crie novas formas, aumente, diminua, amanhã que crie algo novo ou que copie o passado, hoje que mantenha fielmente o desenho e as madeiras, amanhã que arrisque novas combinações.

Os instrumentos têm esta capacidade… são, ao mesmo tempo, ferramenta e obra de arte, representam, ao mesmo tempo, pessoas, colectividades, regiões, países, continentes… Vividos no passado, continuam a ecoar na experiência musical dos dias de hoje, contribuindo para a riqueza da memória sonora colectiva.

A música, como forma de expressão universal, não conhece fronteiras geográficas… é invisível, sem limites. Na sua expressão física nunca teve dificuldade em entrar pelas portas e janelas, ajudada por caminhantes e bagagens, barcos, caravelas, comboios ou aviões. Esta viagem cria novos cruzamentos e sugere, ainda, outros caminhos… a contaminação (inevitável) traz uma nova dimensão ao nosso instrumentário.

(...)

Idanha-a-Nova é um território onde todos estes fios, os que bordam esta tapeçaria de sons, universal e sem tempo, se cruzaram. Um lugar único e especial onde alguns dos fios ficaram (ou mesmo foram criados) e de onde outros partiram ou tantos passaram sem deixar rasto.

Sabemos que a identidade musical deste território gira em torno do adufe, um instrumento singular e emblemático da região, mas sabemos, igualmente, que o património musical de Idanha-a-Nova tem outras dimensões.

(...)

Tal como em 2018, no projecto que desenvolvemos sobre a palheta beirã do pastor José dos Reis e que resultou num novo instrumento, este era um desafio eminentemente criativo, a partir da memória, da tradição, dos tais fios culturais e históricos que bordaram a identidade musical de uma região – e do país – ao longo dos séculos. Seria um novo instrumento, não uma cópia da viola beiroa.

(...)

Both a tool and a work of art EXCERPT

Filipe Faria

The tapestry embroidered by the elements of Portugal's musical heritage is a reflection of intersecting cultural and historical threads that over the centuries have moulded the country's musical identity. Our folk musical instruments, as we know them today, are the result of the inevitable contamination of travels, personal tastes, individual experiences, and collective needs. Evolution is inevitable — I don't have that type of wood today, tomorrow I'll get a different one, today they ask me to create new forms, to make it bigger, smaller, tomorrow they will ask me to create something new, or to copy something from the past, today to faithfully maintain design and woods, tomorrow to develop new combinations.

Instruments have this ability. They are both a tool and a work of art. They represent people, communities, regions, countries, continents. Having lived in the past, they continue to echo in today's musical experience, contributing to the richness of the collective sonic memory.

Music, as a universal form of expression, knows no geographical boundaries. It is invisible and has no limits. In its physical expression, it has never found it difficult to enter through doors and windows, aided by walkers and luggage, boats, caravels, trains or aeroplanes. This journey creates new crossings and suggests new paths. The (inevitable) contamination brings a new dimension to our collection of instruments.

(...)

Idanha-a-Nova is a territory where all these threads, those that embroider this universal and timeless tapestry of sounds, have crossed paths. A unique and special place where some of the threads remained (or were even created) and from where others left and so many passed through without a trace.

We know that the musical identity of this territory revolves around the adufe, a unique and emblematic instrument of the region, but we also know that Idanha-a-Nova's musical heritage has other dimensions.

(...)

As in 2018, in the project we developed around the palheta beirã of shepherd José dos Reis, which resulted in a new instrument, this was an eminently creative challenge, based on memory, tradition, the cultural and historical threads that have embroidered the musical identity of a region – and the country – over the centuries. It would be a new instrument, not a copy of the viola beiroa.

(...)

Na matéria do diálogo

Paulo Longo

Os princípios da intervenção cultural do Município de Idanha-a-Nova são matéria de reflexão, discussão, reconhecimento e desacordo, permanentes.

E ainda bem que assim é. A qualquer estratégia de desenvolvimento que se quer transversal e diversa, seja em que área for – e, decididamente, na cultura – o diálogo, sob as suas múltiplas formas, é ferramenta essencial para aferir o grau de dinamismo presente nesse território. Para o bom, e o menos bom. O consenso generalizado não é, necessariamente, o melhor sinal neste domínio – como também não o é, certamente, a ruptura irredutível – pois ambas deixam de lado o diálogo entre as partes que têm de projectar e construir futuros.

Hoje, como ontem, o processo que medeia tradição e renovação constrói-se, precisamente, na matéria do diálogo, entre legado e visão, num processo exigente e moroso. A ausência de riscos é pura ilusão e não há como contorná-lo – ainda assim, é preferível corrê-

-los do que não o fazer de todo e ficar escondidos na paz podre do indiscutível ou do inquestionável. Esta percepção afigura-se singularmente pertinente no domínio que nos traz aqui. Se há algo que podemos – e devemos – aprender nas propostas desenvolvidas sob a direcção de Filipe Faria, é que vale a pena arriscar, com coragem e responsabilidade, sem fechar futuros à chave.

A tradição tem, em si, o germe criativo da renovação e, sempre que os seus horizontes foram limitados, os resultados não foram felizes. Sim, felizes num sentido seminal e não no sentido dos afectos que hoje servem de referência um pouco a propósito de tudo, quando se quer tocar na área das emoções e que, não raro, se fica pela identificação da memória pela saudade.

Fazer brilhar os olhos a alguém rebuscando passados é uma coisa; outra é suscitar esse brilho olhando para diante. A diferença estará, precisamente, nesse grau diáfano de felicidade, apenas diferente, sem hierarquizar.

Este é um desafio extraordinário, e há que acreditar nele com empenho. Sobretudo aqui onde estamos, naquele que é, para alguns, o lugar mais bonito do mundo. Um lugar onde a Música é matéria viva que contribui para consolidar o reconhecimento das competências e potencial do mundo rural num horizonte do tamanho do mundo, passo a passo.

Este é um desses contributos, muito especial e singular – quase irreal, dir-se-ia. E, uma vez mais, para lá dos conceitos, há um gesto que sobressai no processo deste diálogo estabelecido entre tempo, espaço, matéria, som, que resgata identidades e memórias. Um gesto de criação, que se reconhece a cada corda dedilhada. De irreprimível felicidade, para quem se atrever.

On the subject of dialogue

Paulo Longo

The principles of cultural intervention by the Municipality of Idanha-a-Nova are a matter of constant reflection, discussion, recognition and disagreement.

And that's a good thing. For any development strategy that wants to be transversal and diverse, in any area – and most definitely in culture – dialogue, in its many forms, is an essential tool for gauging the degree of dynamism present in a territory. For the good, and for the not so good. General consensus is not necessarily the best sign in this regard – though neither is an unbridgeable rupture – because both neglect dialogue between parties that have to plan and build futures together.

Today, as in the past, the demanding and time-consuming process that mediates tradition and renewal is built precisely on dialogue, between legacy and vision. The absence of risk is an illusion – there's no way around it – yet even so, it's better to take risks than to do nothing at all and remain mired in the decaying tranquillity of the indisputable or the unquestionable. This insight seems uniquely pertinent in the field that concerns us here. If there's one thing we can and should learn from the proposals developed under Filipe Faria's direction, it's that it's worth taking risks, with courage and responsibility, without locking futures away.

Tradition holds within it the creative germ of renewal; whenever its horizons are limited, the results are not happy. Happy in a seminal sense rather than in the sense of the emotions, which today are used as a reference point for everything and which, not infrequently, confuse nostalgia with memory.

It's one thing to make someone's eyes sparkle by digging into the past; it's another to make them sparkle by looking ahead. The difference lies precisely in that diaphanous degree of happiness, just different, without imposing hierarchies.

This is an extraordinary challenge, and we must believe in what we are doing wholeheartedly. Especially here where we are, in what is, for some, the most beautiful place in the world. A place where Music is a living material that contributes to consolidating the recognition of the skills and potential of the rural within the broader world, step by step.

This is one of those contributions, special and unique – almost unreal, one might say.

And once again, beyond the concepts, there is a gesture that stands out in the process of this dialogue established between time, space, matter and sound, which rescues identities and memories. A gesture of creation that is recognisable with each string that is plucked. Of irrepressible happiness, for those who dare.

Dos ramos de várias árvores EXCERTO

Orlando Trindade

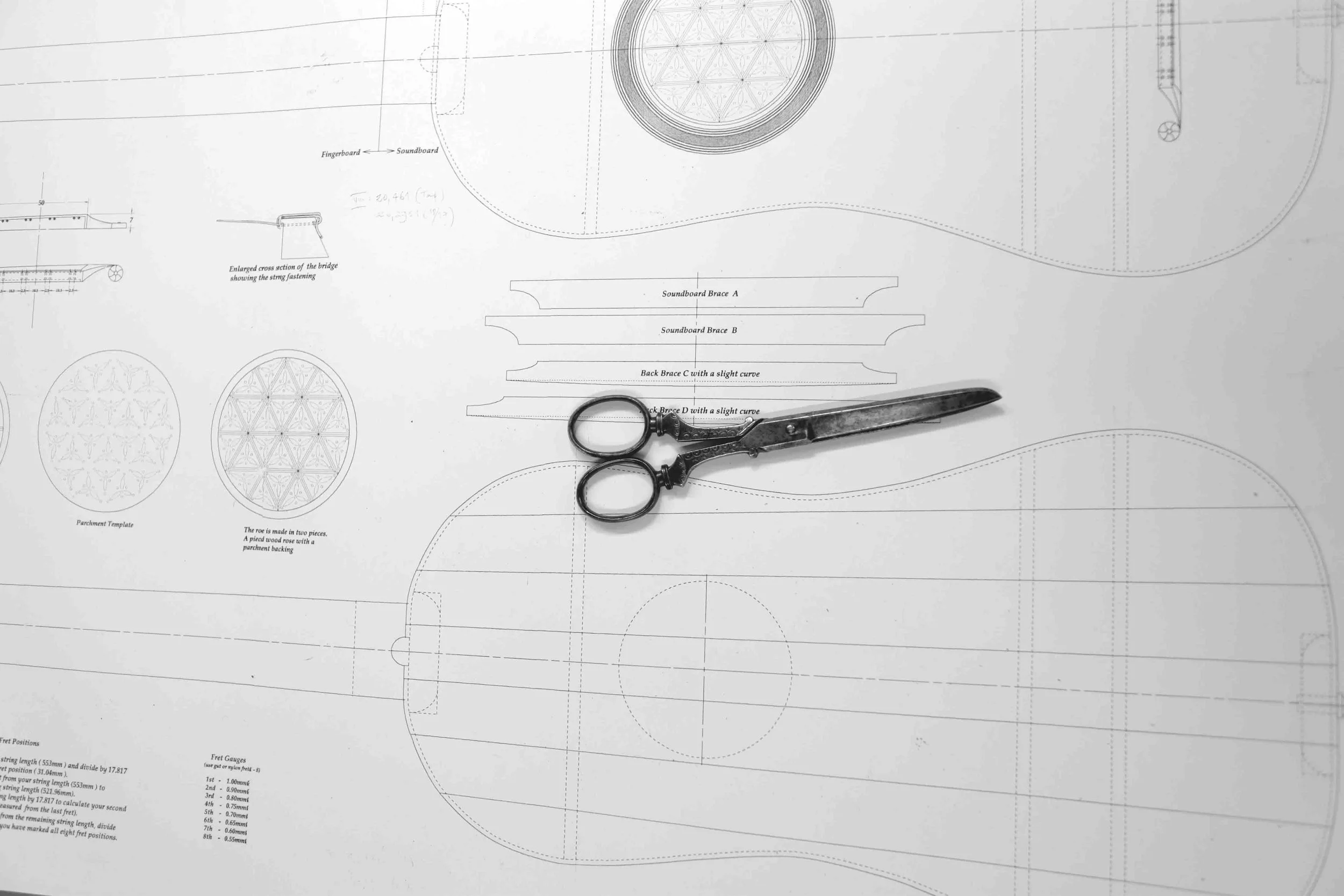

Tudo começou com um telefonema do Filipe Faria propondo-me a construção de duas violas: uma viola de quatro ordens renascentista e uma reinterpretação de uma viola popular, neste caso a beiroa. Desde logo achei que a viola renascentista teria de partir do exemplar mais antigo que chegou até nós, e que se encontra actualmente no museu dos instrumentos musicais do Royal College of Music, em Londres, em cuja etiqueta se pode ler: "Belchior Dias a fez em Lisboa no mês de Dezembro de 1581". Para além de ser portuguesa, e a mais antiga que se conhece, tem também a raríssima característica de ter o fundo composto por sete aduelas dobradas em meia cana e arqueadas longitudinalmente, uma técnica elaborada e virtuosa que aparece referida em alguns documentos, como num texto de 1638 no qual se diz que Manuel de Vega fez uma guitarra de tamanho médio com o fundo canelado feito de ébano de Portugal, "hevano de Portugal… el suelo tumbado e acanelado…".

Em relação à reinterpretação da viola beiroa – a nova bandurra descante –, iríamos partir das violas mais antigas sobreviventes, dando especial ênfase e importância ao instrumento que pertenceu a Manuel Moreira de Penha Garcia e que se encontra actualmente no Museu Nacional de Etnologia em Lisboa.

Os pressupostos comuns à realização de ambos os instrumentos seriam a redução do comprimento de corda vibrante para 480 mm no caso da viola renascentista e 430 mm na nova bandurra descante, a redução do número de cordas para quatro ordens em ambos os instrumentos e, no caso da bandurra, a alteração do material das cordas para a tripa/nylgut mas mantendo a possibilidade do uso das cordas de arame (metal).

Iniciámos o trabalho de recolha de informação com a elaboração de dois desenhos técnicos no Museu Nacional de Etnologia e um outro no Núcleo Etnográfico da Lousa. Os instrumentos foram cuidadosamente fotografados e medidos com a ajuda de várias ferramentas, nomeadamente um aparelho digital que permite medir as espessuras do tampo harmónico, fundo e ilhargas com grande precisão e de forma não invasiva. No caso da viola renascentista, o modelo foi adaptado a partir do desenho técnico da viola de Belchior Dias feito em 1976 por Stephen Barber.

(...)

From the branches of various trees EXCERPT

Orlando Trindade

It all started with a phone call from Filipe Faria proposing that I build two guitars: a Renaissance guitar with four courses of strings and a reinterpretation of the traditional viola beiroa. I immediately thought that the Renaissance guitar would have to be based on the oldest example that has come down to us, which is currently held in the museum of musical instruments at the Royal College of Music in London, the label of which reads: "Made by Belchior Dias in Lisbon in December 1581." As well as being Portuguese, and the oldest known, it has the very rare characteristic of having a back made up of seven perpendicularly curved staves that are arched longitudinally, an elaborate and virtuosic technique that is mentioned in some documents, including a text from 1638 in which Manuel de Vega is said to have made a medium-sized guitar with a fluted back made of ebony from Portugal, "hevano de Portugal… el suelo tumbado e acanelado..."

For the reinterpretation of the viola beiroa – the new descant bandurra –, we would start with the oldest surviving guitars from the Beiras region, placing special emphasis and importance on the instrument that belonged to Manuel Moreira from Penha Garcia, currently in the National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon.

Assumptions common to the realisation of both instruments were the reduction of the vibrating string length to 480 mm in the case of the Renaissance guitar, and to 430 mm in the case of the new descant bandurra; the reduction of the number of strings to four courses for both instruments; and, in the case of the bandurra, to change the string material to gut/nylgut while maintaining the possibility of using wire (metal) strings.

We began the task of gathering information by drawing up two technical drawings at the National Museum of Ethnology and another at the Lousa Ethnographic Centre. The instruments were carefully photographed and measured with the help of various tools, including a digital device that allows us to measure the thickness of the soundboard, bottom and sides non-invasively and with great precision. In the case of the Renaissance guitar, the model was adapted from the technical drawing of the Belchior Dias' guitar made in 1976 by Stephen Barber.

(...)